Brazil | HR | RURAL VIOLENCE

With Ronilson Costa

“The perpetrator of these crimes is agribusiness”

The murder of British journalist Dom Phillips and indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and the confirmation, on June 16, of the discovery of their dismembered and burnt bodies shocked the world. This violence, however, committed under the cloak of impunity and fueled by the current government’s hate speech, is something that native peoples and their defenders have been suffering for decades.

Amalia Antúnez

21 | 06 | 2022

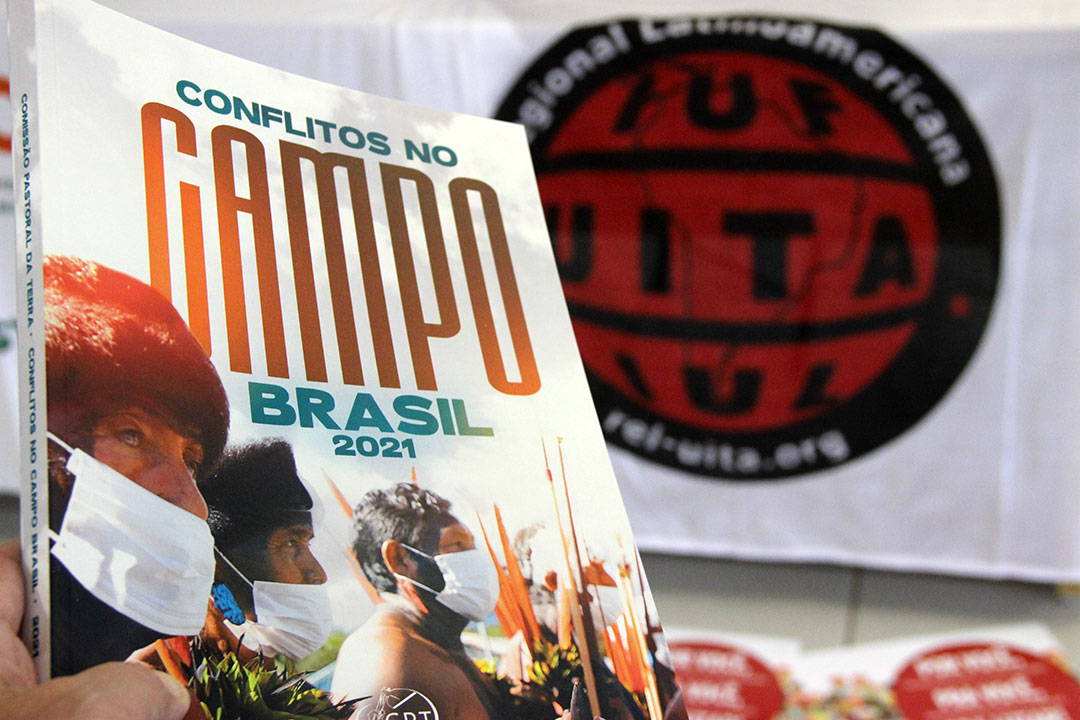

Foto: Gerardo Iglesias

“This was a high-profile case because one of the individuals murdered was a journalist and the press gives special coverage when one of their own is killed, and also because he was a foreigner and the crime was committed in an area where the situation is desperate,” Ronilson Costa, a priest who is national coordinator of the Pastoral Land Commission (Comissão Pastoral da Terra, or CPT), said in conversation with La Rel.

Costa explained that the southwest region of Amazonia is one of the most highly disputed areas and where the greatest number of land conflicts occurs.

“CPT activists working in the area tell us of the enormous difficulties they face in their efforts to defend the environment, land rights, and indigenous communities and other populations,” he said. According to Costa, the origin of these conflicts is the expansion of agribusiness across the states of Mato Grosso and Rondônia, and now the southern region of the state of Amazonas and all of Acre.

Agribusiness now dominates this whole region and it is often the same large landowners and soybean growers who are in Paraná, São Paulo, Goiás, and Tocantins and who have the full support of this government that encourages the sector to advance on territories already occupied by traditional communities,” he denounces.

The priest also warns about the Jair Bolsonaro government’s nod to the garimpeiros (illegal miners), with his announcement that this practice will be legalized, and that, if indigenous people do not want to plant soybean in their lands, they can rent them out to producers who do want to grow these crops.

“This is something that happens in practice with several indigenous lands, something that is illegal according to the Constitution of the Republic, as is grilagem (the appropriation of public lands), and which is supported by government projects and is part of the illegal land business game in the Amazon region.”

For the CPT coordinator, Amazonia has ultimately become the main site for the expansion of agribusiness, illegal mining, illegal logging, and more recently drug trafficking and the activities of criminal factions that were operating in Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo and now offer their services to those conducting illegal business on Amazon lands.

“Of the 35 murders of rural activists, indigenous leaders, environmentalists, and human right defenders committed in 2021, 28 were committed in the Amazon region. And this year, of the 19 cases registered thus far, 15 were in Amazonia”, Costa reports.

The murder of the Brazilian indigenous advocate and the British journalist was shocking because of its viciousness, but, according to Costa, brutality has characterized crimes in this region for some time now and it is a sign of the degree to which organized crime has advanced.

“The strategies for disappearing the bodies to hinder their discovery and the barbarity of the acts denote a structured and systematic work,” he underlines.

Organized crime in rural areas is not new. Hit men, militia, and military police have always been hired to eliminate environmental and indigenous community defenders or to force peasants and traditional peoples off their lands if they threaten the interests of certain economic or political groups. It is a practice that dates back decades.

From Chico Mendes and Dorothy Stang to Zé Claudio and Maria, Paulinho Guajajara, and more recently Zé do Lago and his family, there are thousands of environmentalists, defenders of traditional peoples’ rights, and trade unionists who have died at the hands of gunmen hired by large landowners, loggers, grileiros, and miners.

“CPT members themselves are constantly threatened, not just because of our work in rural areas, but also because of any crimes we report. And when we go to those areas, we can’t use anything that may identify us; we can’t even ask for a receipt if we buy something.”

Costa is outraged as he recalls Bolsonaro’s statements regarding the Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira case.

“The president blames the victims for what happened to them, and that discourse emboldens those who kill, those who invade communities, because they see themselves in Bolsonaro and treat us as enemies.”

“But we can’t lose hope that this situation will change,” he adds. “We have already realized that this change is not going to come from any government, so what is left for us to do is resist alongside these communities. Fight and resist,” he concludes.

The map of impunity

From 1985 to 2021 there were 1,536 murder cases in rural areas, with a total of 2,028 victims. Of those cases, 170 went to trial, with 39 individuals accused of ordering the murders found guilty and 34 acquitted, and 139 individuals accused of being the material perpetrators sentenced and 244 acquitted.

According to data from CPT, 88.94 percent of murder cases did not make it to court, revealing that impunity is used as a tool in the forcing of rural people from the lands, forests, and waters in their territories.

In the last ten years, 313 people were murdered in the Amazon region in rural conflicts, accounting for 77 percent of the 403 such murders committed in all of Brazil from 2012 to 2021.

Last year saw the highest number of murders recorded since 2017, with 28 people killed in the states that make up the Amazônia Legal (the seven North Region states plus Mato Grosso and Maranhão).

Not counting Bruno and Dom, the CPT has recorded 19 murders in rural areas thus far this year. Of those, 15 were in Amazonia.