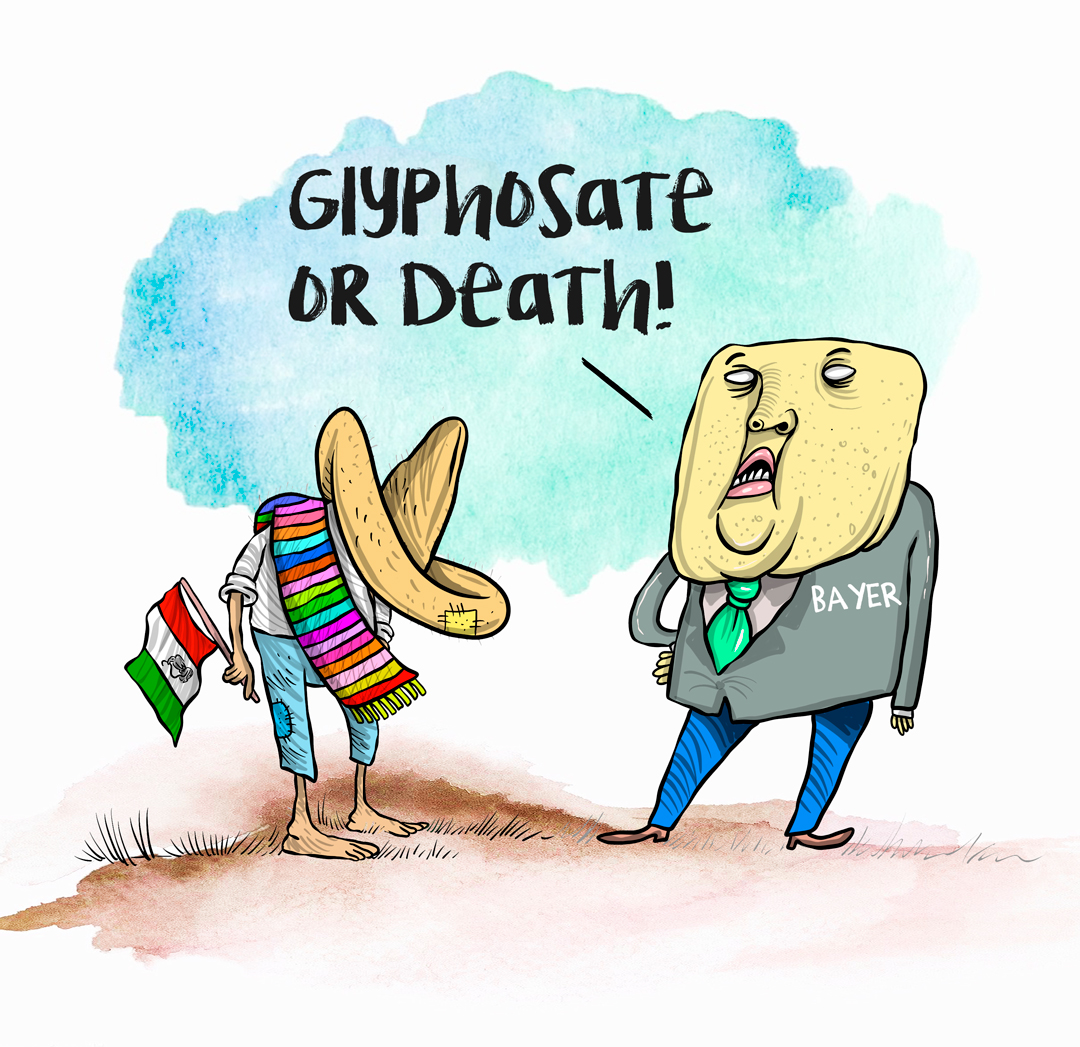

Mexico | BAYER | AGROCHEMICALS

Bayer pressures Mexico to abandon glyphosate banning plans

The usual suspects

In what could be seen as a sequel to the famous Monsanto Papers (a series of documents revealing the methods employed by that transnational corporation to discredit those who were denouncing the harmful effects of its products and the pressure exerted by the company on governments, politicians, and scientists), the British newspaper The Guardian has just uncovered similar tactics used by Bayer, Monsanto’s current owner, to make Mexico abandon its decision to ban glyphosate.

Daniel Gatti

Illustration: Allan McDonald

Drawing on documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request filed by the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), the British daily notes that Bayer acted in conjunction with high U.S. government officials under the Donald Trump administration, as well as with lobbying organizations representing companies that produce genetically engineered seeds.

The Guardian was unable to determine whether the Joe Biden administration was continuing along the same lines.

For 18 months, senior executives of the German company, along with the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agricultural Service, all United States government bodies, pressured members of the Mexican government with the aim of dissuading it from banning glyphosate spraying.

(It should be noted that during the Trump years the EPA was an oxymoron, as he led the dismantling of the—few and modest—environmental protection laws passed under the Barack Obama administrations.)

In one of the few decisions that honor his promises of defending food sovereignty and protecting the health of workers and the environment, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, had widely announced a plan to end glyphosate use on Mexican fields by 2024.

On December 31, 2020, the government issued a decree to that effect.

Bayer admitted to The Guardian that as soon as it learned of the Mexican government’s plans it sprang into action.

“Like many companies and organizations operating in highly regulated industries, we provide science-based information and contributions to regulatory and public policy-making processes,” the company’s representatives in Mexico said.

And they insisted with a lie that agrochemical companies and some governments, most notably the government of the United States, keep repeating: that “there is no scientific evidence” of the harmful effects of glyphosate.

Tangible proof that scientific evidence does exist is the billions of dollars that Bayer has had to pay in compensation to hundreds of U.S. farmers who have filed claims against the company for the harm that this toxic agrochemical has caused them, their families, and their environment.

The transnational corporation did not pay such fortunes because it wanted to, but because it was ordered to pay in a series of court decisions that recognized the validity of the scientific literature and the testimonies that reveal the harmfulness of glyphosate.

The Guardian cites a staggering number of emails sent to Mexican authorities by executives of both Bayer and other companies in the industry gathered in a lobby called CropLife, and by USTR chief Robert Lighthizer himself, threatening Mexico with retaliation if it went ahead with its glyphosate banning plans.

According to internal communications, one of the strategies used by these industry executives, the USTR, and the EPA was to push for the United States to “fold this issue” into the United States-Mexico Canada Agreement (USMCA), with the USTR then telling Mexico its glyphosate ban could be considered an instance of noncompliance.

In one email reviewed by The Guardian, for example, Lighthizer warns Graciela Márquez Colín, Mexico’s minister of economy that “glyphosate issues” could hurt bilateral relations with the United States.

In another email Mexican government officials are described as “vocal anti-biotechnology activists” and the Latin American country’s Federal Commission for Protection against Health Risks (Cofepris) is identified as “becoming a big time problem.”

Also mentioned are messages from CropLife president Chris Novak to Lighthizer, alerting him that Mexico could apply to other pesticides the same principle cited by the country for phasing-out glyphosate (the precautionary principle).

“If Mexico extends the precautionary principle, $20 billion [dollars] in annual U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico will be jeopardized,” Novak wrote in a bid to appeal to Lighthizer and urge him to act at “the highest political level.”

Corn exports to Mexico currently bring in some 3 billion dollars a year for the United States. Ninety percent of that corn is genetically engineered.

The Guardian informs that the same pressures exerted on Mexico over the course of 18 months were also exerted earlier on Thailand, and it recalled the “Monsanto Papers” published in 2019 in France, in which the ugly workings of the then U.S.-based transnational corporation were laid bare.